I found myself this week thinking about the ways in which various languages treat humans and animals differently from other nouns. It was at first a thought I had whilst trying to distract myself from learning the highly irregular declension tables of the Russian дочь (daughter) and мать (mother). I wondered why I had encountered on so many occasions that family members are irregularly declined and bear characteristics that do not follow conventional paradigms. The other example that sprung to mind was the fact that أخ ,عم and أب (uncle, brother and father) are all declined irregularly in Arabic, taking an extra long vowel instead of the standard suffixes in the nominative, accusative and genitive. In Arabic due to the suffix -ة there is no possibility (to my knowledge) of encountering an irregular feminine noun, so their feminine equivalents are totally predictable. There are all kinds of reasons for these phenomena, the most common one thrown out is that it is because kinship terms are so commonly used and often abbreviated for reasons of affection and therefore the nouns experience an unusual level of non-standard morphology. But all this declension talk is not that fun- let’s take a look at some of the other ways in which languages privilege human subjects above their inanimate counterparts.

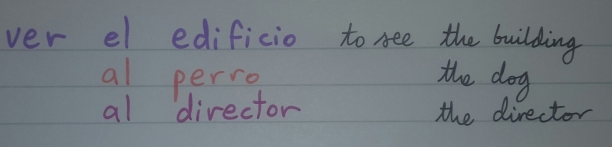

The most basic one is a feature so ingrained in the minds of Spanish speakers that it’s easy to forget. A transitive verb is one that takes a “direct object” and in practice is a verb that can be directly followed by an object with no preposition in between to modify the act- an example in English is “see”. You see a building and you see an engineer. In Spanish though, somewhat oddly, the human or animal subject of a transitive verb takes the preposition “a” (“to”). You Spanish, you ves un edificio (see a building) but ves a un ingeniero (see an engineer). Nobody ever thinks about this because its a very minor thing to adjust to and is seldom considered in any depth, but in theory it means that verbs that ordinarily take an accusative object, if the object is a person or animal, take a dative object.

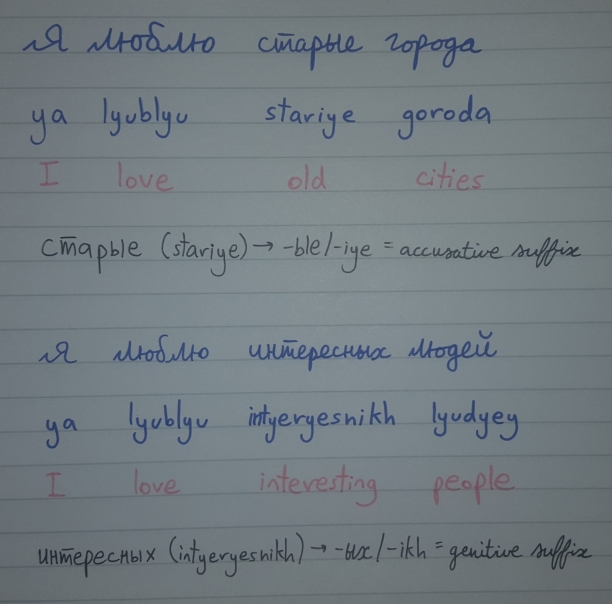

The other salient example of this happening is in Russian. Masculine and neuter nouns (if they refer to animate beings) are declined according to the genitive paradigm, rather than the accusative, even though the verb is transitive and should, logically, have an accusative object. It is true for plural nouns of all genders (although the only animate neuter noun is лицо); the plural accusative and genitive suffixes are -ые and -ых respectively, and in the examples we see below it is seen that when the object of the verb любить- to love- is an inanimate noun (a city), it is declined as accusative, but if it is animate (people) then it needs to be genitive.

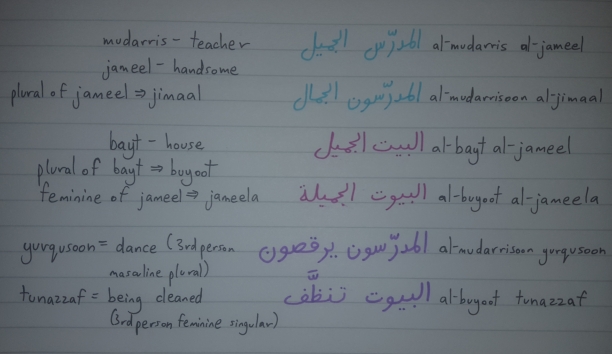

When you learn Qur’anic Arabic grammar, you spend an absolute age learning the 40 or so different methods or plural formation. They are massively unpredictable and, now that I’ve had them under my belt for many years, quite charming, but it is no doubt annoying that the plural of باب (baab- door) is أبواب (abwaab), whereas the plural of كرسي (kursiy- chair) is كراسي (karaasiy). But there is one category of nouns that can be pluralized in a fairly regular way- humans. The suffixes ون (oon- massculine) and ات (aat- feminine) are for the most part only seen with human nouns, although by no means do ALL human nouns take these regular suffixes. An engineer is مهندس (muhandis) and engineers are مهندسون/ات (muhandisoon/aat), which compared to the nightmarish irregularity of non-human nouns is a breath of fresh air.

Humans also differ in a further respect as far as Arabic is concerned; non-human nouns are considered to be, if pluralized, grammatically feminine singular. That means that in the Arabic sentence “the door creaks” the verb “creak” is conjugated not in the 3rd person plural as it would be in most other languages, but in the 3rd person feminine singular (“she”). The example of al-buyoot tunazzaf below shows this. Similarly when declining the adjectives that modify plural nouns, if the noun is not human, then its modifying adjective should not be plural, but feminine singular.

The practice of using “counting words” is not rare, especially in languages of East Asia. The system is generally that instead of simply using numerals and the nouns that they count, there is a buffer word which relates to the noun. Measure words divide nouns into classes- in Chinese, Japanese and Korean there’s a system that is (almost) shared, which includes a generic counter (个/개/つ) and various more specialised counters that cover other categories of nouns, for example we have 只/마리/匹 which are respectively the Chinese, Korean and Japanese words used for counting (some/most/all) animals (pronounced zhi, mari and hiki respectively).

Some languages however only have a single split in the way they allocated their measure words: you guessed it- human and non-human. It wouldn’t surprise me if there were dozens of such languages, but the three I’ll focus on here all belong to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family: Bengali, Nepali and Farsi.

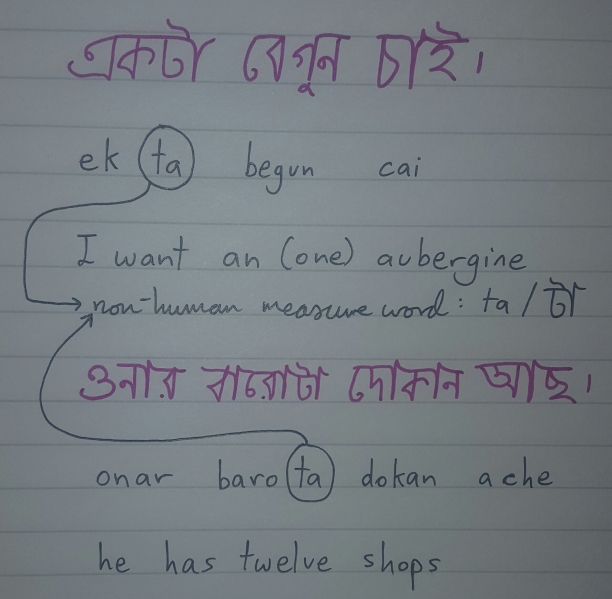

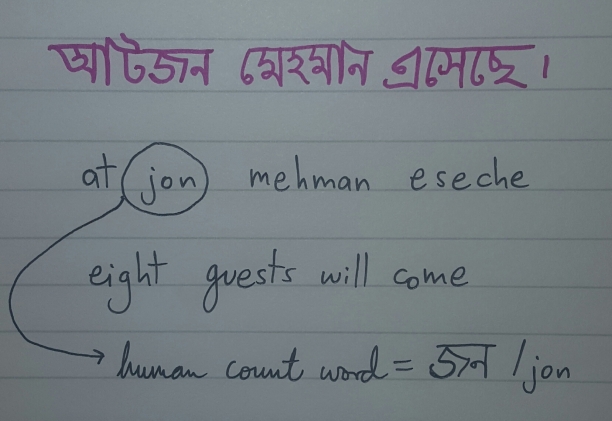

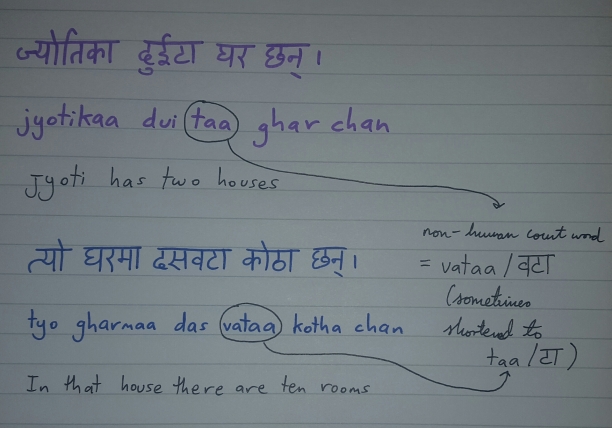

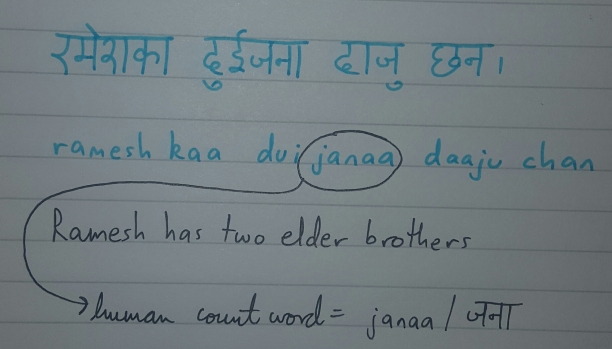

Those of Bengali and Nepali are actually the same I realsied, after mentally decoding the Devanagari script into the also Sanskritic and only slightly different but somehow infinitely trickier Bengali script. A counter exists for humans (jana जना/jon জন) and for non-humans (ta টা/vataa वटा). Look at how these work below.

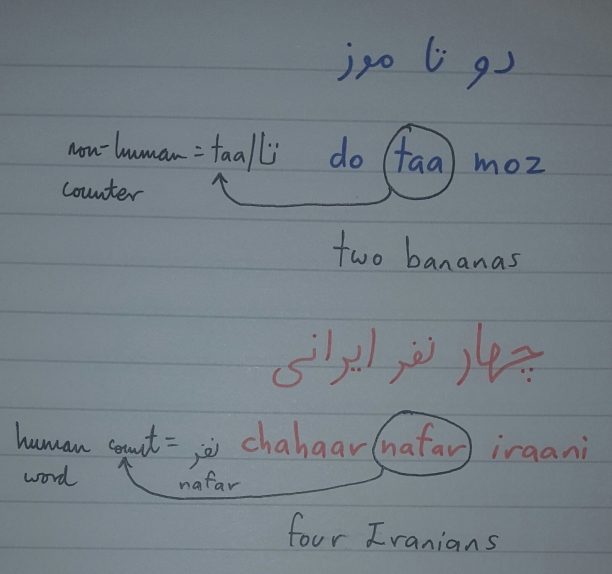

Farsi plays a bit more fast and loose with these words (which are تا ta, like Bengali, for non-humans, and نفر nafar for humans), but in properly spoken Farsi they should be employed more or less all the time.

I’m sure the usual will happen and as soon as I’ve published this, another 5 examples of languages that for no good reason grammatically distinguish between human and non-human nouns (omg literally just now thought of one, oh well, to be posted another time). I suppose the point of this post is to encourage you to question the things that you take for granted in language and wonder whether or not they are features which tell us a bit about societal and cultural norms reflected in language. It’s easy to accept as law the rules of grammar, less simple and more rewarding is to philosophise and try to imagine where these little oddities come from, and what purposes they may serve.

Recent Comments