I’ve just got back from one of the most fun holidays of my life. I think a trip’s enjoyability is massively influenced by the life that you’re coming back to at the end. In the case of this trip, Air France’s entire team of stewards had to restrain, drug and haul my weeping and uncooperative corpse onto the plane once I realised that the only thing keeping me from returning to work was a 12 hour flight.

This trip has been the first time in around a year and a half that I’ve been so completely immersed in and surrounded by the Korean language, so I took some notes on my experiences and the things that surprised me, as well as those that were just as expected. One of the reasons for going on this trip was to prepare for the TOPIK (Test of Proficiency in Korean) that I plan to take this coming spring, and spending a couple of weeks eavesdropping on conversations on buses and watching the Korean news (which is more right wing than I knew before!) has been really helpful prep.

- Honorific, polite and respectful language not as useful/necessary/common as I previously thought

This one shouldn’t have shocked me. In my final year of university I was studying sociolinguistics and the ways in which language and power interact with one another. A Japanese-American academic who supervised me told me that whilst carrying out research in Japan, they had been constantly complimented by Japanese people born in the 30s and 40s for her proper and precise use of honorific grammar and vocabulary. It’s because being Japanese raised overseas, she had been educated and taught Japanese language outside of the sphere of social and linguistic norms of Japan; whereas during her lifetime formal language had fallen out of favour among Japanese teens and young people, in her house there was no such social change.

I am not a Korean raised overseas; I’m a total foreigner who has learnt Korean to some extent (limited, poor, interesting or excellent depending on which of my Korean friends you decide to ask). Having lived in China one three occasions totalling a fairly long time, I have become aware of how useful it is in forming relationships to use the proper forms of address, especially with older people. Even in a shop, addressing the proprietor as auntie before your request notably softens the tone and makes the 阿姨 ayi, or auntie in question much more at ease and amenable. So I took the same idea to Korea and on a few occasions it paid off. Below are a few examples:

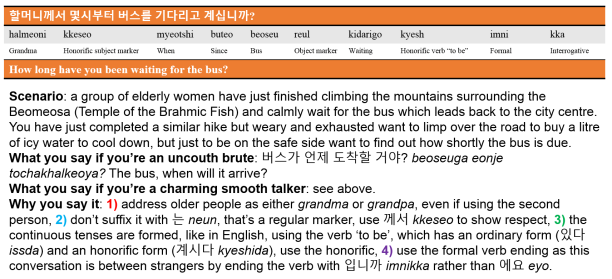

Halmeonikkeseo myeot shi buteo beoseureul kidarigo kyeshimnikka?

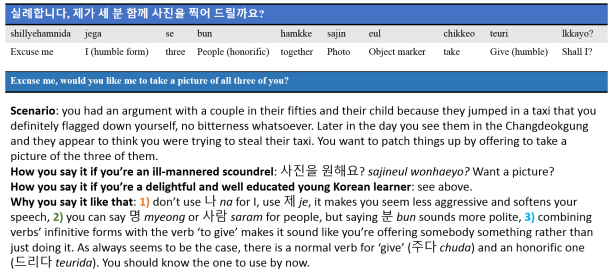

Sillyehamnida, jega se bun hamkke sajineul chikkeo teurilkkayo?

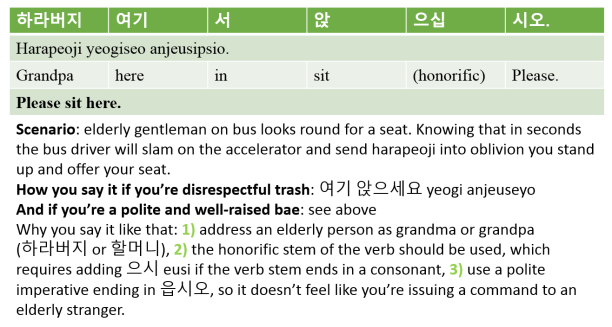

Harapeoji, yogiseo chom anjeushipshio.

So few foreigners speak Korean that even if I had used regular language I doubt there would have been any negative reaction. It is however quite endearing to use both humble and respectful language- it demonstrates an appreciation of the culture in which a language has developed rather than simply an ability to learn words and grammar.

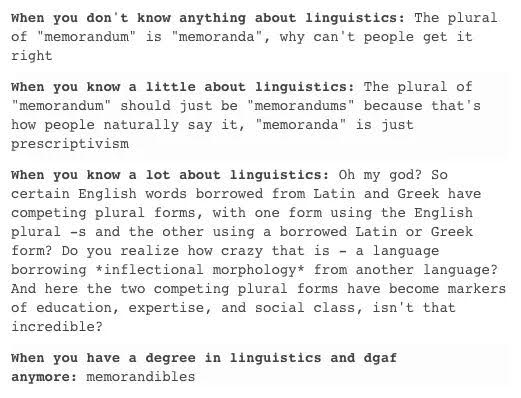

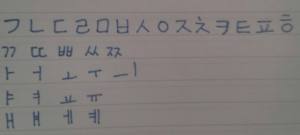

Necessary though? I would have to say absolutely not. Whilst the language I was using did not seem unusual to the audience, it would almost certainly surprise my Korean contemporaries (i.e. 20-somethings). In interactions that I observed between young and older Koreans, it was very rare for me to hear the respectful register being used. This isn’t news in the grand scheme of the Korean language; there were originally seven registers of varying formality and politeness, and now only four are commonly in use. Potentially in just a few generations we will see two or three of the remaining ones dwindle into disuse.

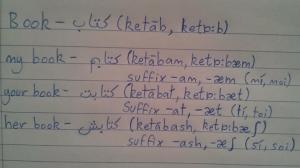

- Can’t rely on foreign imported vocabulary so much

This was a foolish error on my part. In most languages you do need to actually learn words in order to communicate. This year however I spent so much of my time both learning and speaking Hindi and Urdu with native speakers that I became quite lazy.

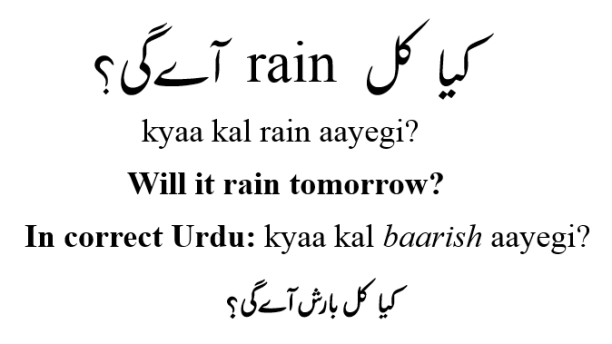

Wanna ask if it’s raining, but forgot the Urdu word for rain? Just say rain:

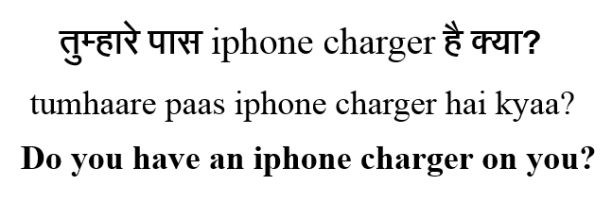

Need your phone charger, but not sure how to say it in Hindi? No worries:

Want to send a postcard from Korea to Canada? Well, you should probably know the word 엽서 yeobseo, because you can’t just walk into a post office and say 안녕하세요, 이 postcard 을 캐나다에 보내고싶습니다 because. It. Doesn’t. Mean. Shit.

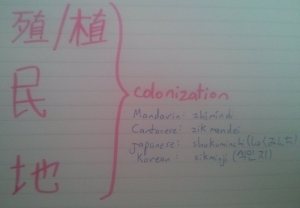

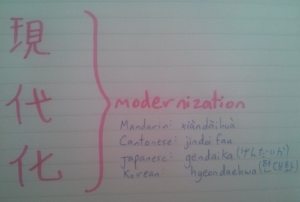

- The semantic relationship with Chinese is more useful than anticipated

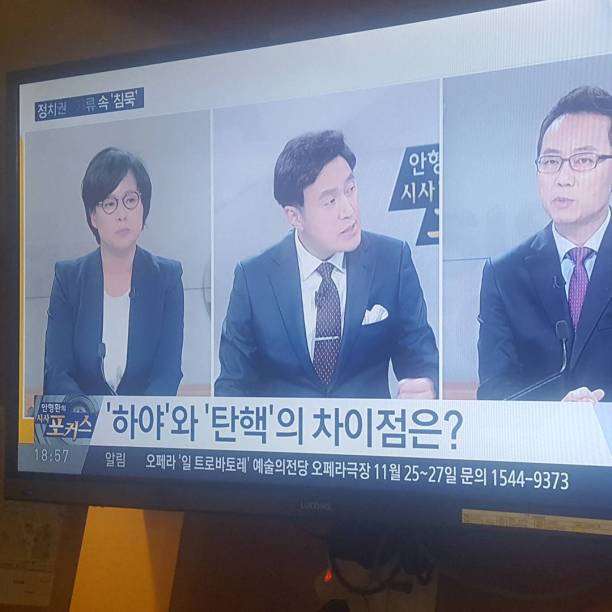

On my final day in Seoul the new channel that I was watching announced that large scale protests calling for the resignation of President Park Geunhye were taking place in Gwanghwamun Plaza, directly south of the Gyeongbok Palace, the historic and cultural centre of Seoul. My couchsurfing host was complaining about the high level political vocabulary that was being used by news outlets to discuss the calls for impeachments.

“It really irritates me, our whole lives we’re taught that 탄핵 danhaek means impeach, and now suddenly no one is using it and they’re saying 하야 haya instead. You have to learn a whole new language to watch politics in Korea, it’s bullshit.”

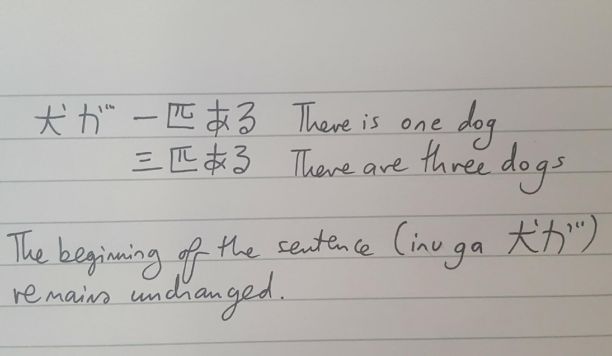

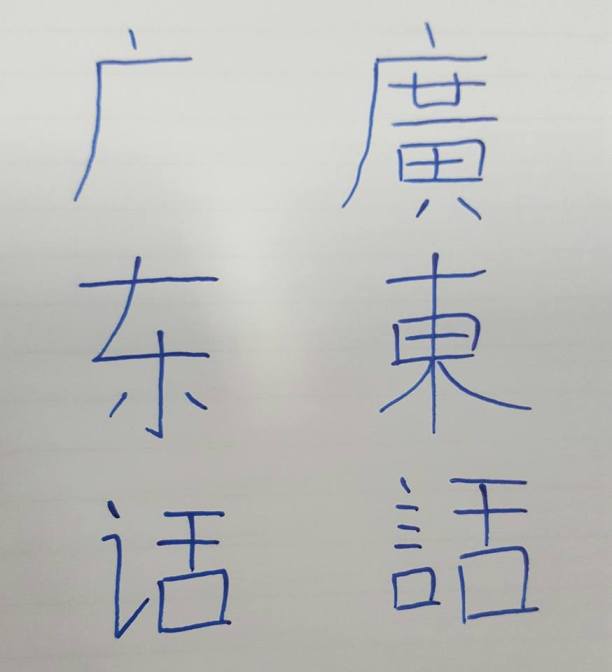

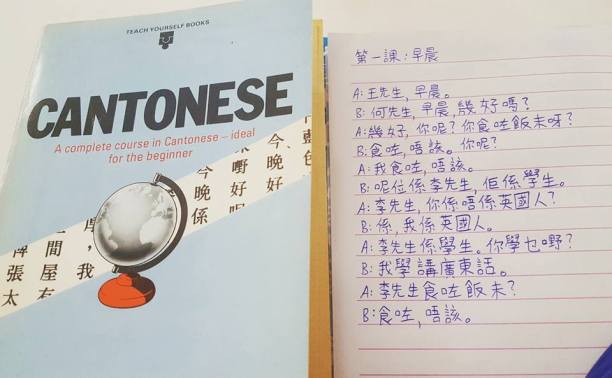

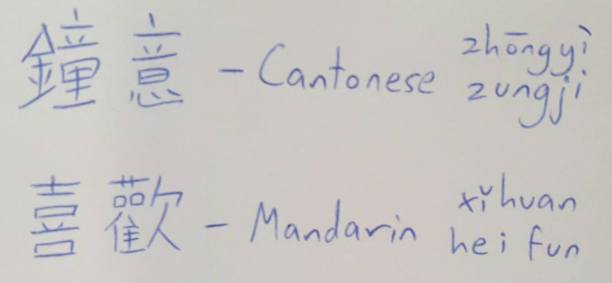

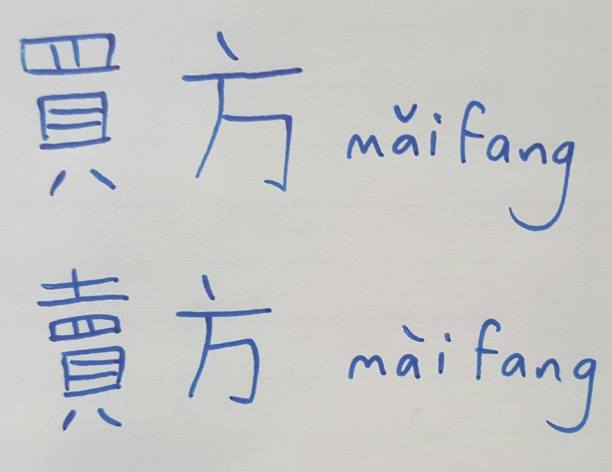

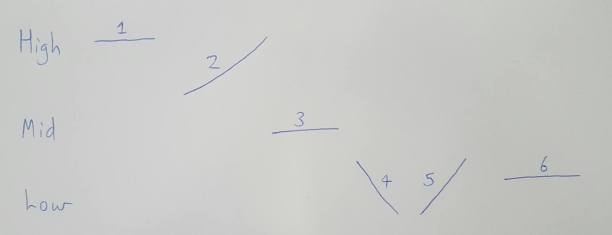

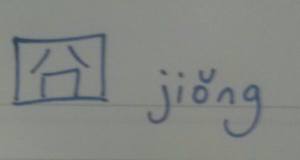

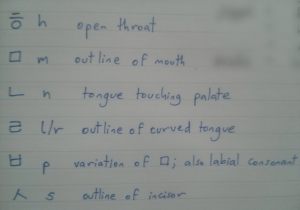

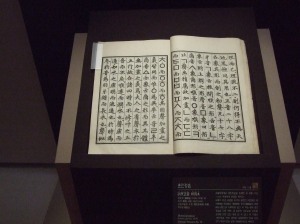

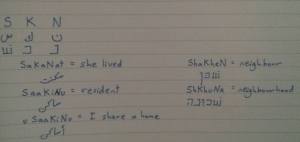

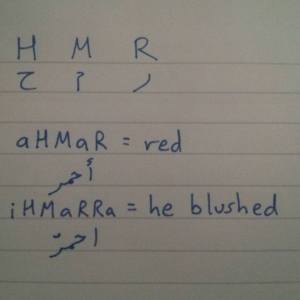

I chewed over this for a moment. Quite often in Korean there exist two words for the same thing- it’s the same phenomenon that appears in Japanese. One of these words is pure Korean in origin, and the other is Chinese. Once you’re familiar enough with both languages it’s easy to identify. Almost every verb in Korean is pure Korean, unless it ends in 하다 hada, in which case it is probably Chinese. For example 내리다 naerida means to get off a bus, and so does 하차하다 hachahada. As a Chinese speaker and user I find hachahada (which comes from the phrase 下车 haa che/xia che in Chinese) more convenient and pleasant to use, but most Koreans unsurprisingly feel the opposite. My first thought was that one of danhaek and haya would be Korean and one Chinese. However looking at them, it’s very clear that they’re in fact both Chinese. Danhaek (impeach) is the characters 弹劾, which are pronounced in Cantonese as tanhaat. Haya was less obvious, but the Chinese character 下 xia/ha (to put down or descend) is always pronounced as ha in Korean (like in hachahada above). I was able to explain just from knowing this that the reason different words are being used is because they have different meanings, danhaek meaning to impeach (a transitive verb) and haya meaning to give up power, or abdicate (which I later confirmed is derived from the archaic and truly out of date 下野 haaye/xiaye).

Being surrounded by a language all day isn’t just the best way to learn it, as clichéd language teachers have been insisting all our lives. It’s also the most enjoyable way to further explore and understand the social and psychological environment that both shapes and is shaped by language. I hope following this trip I’ll be able to write more deeply about the linguistics of Korean and of learning this language, as well as the ways in which it interacts with other languages, both Indo-European and within the context of East Asia.

Recent Comments